Restless Nights: Understanding and Managing Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless Nights: Understanding and Managing Restless Legs Syndrome

Explore the intricacies of Restless Legs Syndrome, which significantly affects sleep and daily life. Uncover the latest in diagnosis, treatment, and its profound impact on mental and social well-being.

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), is a neurological disorder characterized by an overwhelming urge to move the legs. This sensation often accompanies uncomfortable and unpleasant feelings in the legs, described as crawling, creeping, pulling, throbbing, aching, itching, or electric. These sensations typically occur during periods of rest or inactivity, particularly in the evening or at night, and are temporarily relieved by movement, such as walking or stretching (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2023).

Individuals with RLS often experience significant distress and impairment in social, occupational, educational, or other important areas of functioning due to these symptoms. The disorder can lead to considerable sleep disturbances, with sufferers frequently experiencing difficulty falling or staying asleep, resulting in daytime fatigue and reduced quality of life. The severity of RLS symptoms can vary from mild to intolerable and fluctuate in intensity. Over time, symptoms may gradually worsen and affect both legs. In some cases, the arms or other body parts may also be involved (Garcia-Borreguero et al., 2016).

The pathophysiology of RLS is not entirely understood, but it is believed to involve dopaminergic system dysfunction and iron metabolism. There is also evidence to suggest a genetic component, as the disorder is more common in individuals with a family history of RLS (Winkelmann et al., 2007).

In summary, Restless Legs Syndrome is a condition that significantly affects an individual's comfort and ability to rest, with a notable impact on their overall quality of life. Its management often requires a multifaceted approach, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies.

Diagnostic Criteria

The DSM-5-TR outlines specific criteria for diagnosing Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2023), these criteria include:

- An urge to move the legs is usually accompanied by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs. These sensations typically begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity and are partially or totally relieved by movement.

- The urge to move the legs or the unpleasant sensations begin or worsen in the evening or at night.

- The symptoms are not solely accounted for by another medical or behavioral condition (e.g., leg cramps, positional discomfort).

- The symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The DSM-5-TR (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) provides specifiers for Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) to describe the frequency and severity of the symptoms. These specifiers are essential for clinicians to diagnose and manage the condition accurately. They include:

- Severity Specifiers: The severity of RLS symptoms is categorized based on their frequency and impact on the patient's sleep and daily functioning. The DSM-5-TR outlines the following severity levels:

- Mild: Symptoms occur on average less than twice a week and result in minimal distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- Moderate: Symptoms occur on average more than twice a week but less than nightly, causing moderate distress or impairment.

- Severe: Symptoms occur nightly, resulting in severe distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other vital areas.

- Course Specifiers: These describe the pattern and progression of the disorder over time. The DSM-5-TR recognizes the variable nature of RLS and includes:

- Chronic: Symptoms persist for a significant period, typically over six months.

- Episodic: Symptoms occur for a limited time and may come and go.

- Specifier for Clinical Significance: This specifier indicates whether the symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

It is important to note that while the DSM-5-TR provides a framework for diagnosing mental disorders, the specifiers for RLS, particularly regarding severity and course, are informed by clinical judgment and patient-reported outcomes. These specifiers help clinicians tailor treatment plans to individual patient needs, considering the variability in symptom presentation and impact on quality of life.

Research has significantly contributed to understanding the prevalence and impact of RLS. A study by Ohayon and Roth (2002) indicated that RLS is a common disorder with a prevalence rate of 5.5% in the general population. This study also highlighted the impact of RLS on sleep quality and the increased risk of psychiatric disorders in affected individuals.

Further, genetic studies, such as those conducted by Winkelmann et al. (2007), have identified specific genetic markers associated with RLS, providing evidence for a hereditary component in the disorder. This genome-wide association study identified common variants in three genomic regions, suggesting a complex genetic basis for RLS.

The management of RLS often involves pharmacological treatments, as outlined in the guidelines developed by Garcia-Borreguero et al. (2016). These guidelines recommend dopaminergic agents as the first-line treatment for RLS and addressing any underlying iron deficiency.

In summary, the diagnostic criteria for RLS, as specified in the DSM-5-TR, focus on the urge to move the legs, the timing and triggering of symptoms, and the exclusion of other conditions, underlining the significant impact of RLS on individuals' lives.

The Impacts

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) significantly impacts various aspects of an individual's life, including sleep quality, mental health, and overall quality of life. One of the most prominent impacts of RLS is on sleep. Studies have consistently shown that individuals with RLS often experience difficulties in initiating and maintaining sleep, leading to chronic sleep deprivation (Garcia-Borreguero et al., 2016). This sleep disruption can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness, affecting an individual's ability to function effectively during the day.

The relationship between RLS and mental health has also been a subject of research. A study by Hornyak et al. (2007) found a significant association between RLS and psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety. This is thought to be due to the chronic distress and discomfort caused by RLS symptoms, as well as the sleep disturbances they cause.

Moreover, RLS has been linked to a decreased quality of life. A study by Happe et al. (2008) demonstrated that the severity of RLS symptoms directly correlates with a lower quality of life. This decrease in quality of life is attributed to the chronic nature of the disorder, its impact on sleep, and its association with mental health issues.

The economic impact of RLS is another critical consideration. According to Allen et al. (2014), RLS can lead to increased healthcare utilization, lost productivity, and indirect costs related to decreased quality of life and comorbid conditions.

In summary, RLS is a disorder with far-reaching impacts, affecting not only sleep but also mental health, quality of life, and economic factors. These multifaceted effects highlight the importance of effective management strategies for individuals with RLS.

The Etiology (Origins and Causes)

The etiology of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is complex and thought to be multifactorial, involving genetic, neurological, and environmental factors.

Genetic factors play a significant role in the development of RLS. Studies have identified specific genetic loci associated with the disorder, indicating a hereditary component. A landmark genome-wide association study by Winkelmann et al. (2007) identified common variants in three genomic regions associated with RLS, suggesting a complex genetic basis for the disorder. Further research by Stefansson et al. (2007) expanded on these findings, confirming the genetic susceptibility in RLS and identifying additional genetic markers linked to the disorder.

Neurological factors, particularly involving dopaminergic pathways, are also significant in RLS etiology. Studies have shown that dopaminergic agents can alleviate RLS symptoms, suggesting a dysfunction in the dopaminergic system. This was supported by research by Earley et al. (2014), which demonstrated altered dopaminergic neurotransmission in individuals with RLS.

Iron deficiency has been implicated in RLS. The study by Connor et al. (2009) found that low levels of iron in the brain, particularly in the substantia nigra, are associated with RLS. This suggests that iron plays a role in the neurological processes underlying RLS.

Environmental factors and comorbid conditions can also contribute to the development and exacerbation of RLS. For instance, pregnancy, renal failure, and certain medications are known to be associated with secondary RLS (Becker et al., 2004).

In summary, the etiology of RLS is complex and involves a combination of genetic predisposition, dopaminergic system dysfunction, iron metabolism abnormalities, and environmental influences. This multifaceted origin underlines the challenges in understanding and treating RLS effectively.

Comorbidities

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is often associated with various comorbidities affecting various health aspects. These comorbid conditions can exacerbate the symptoms of RLS and complicate its management.

One of the most common comorbidities of RLS is sleep disturbance, including insomnia and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD). Studies have shown that many individuals with RLS experience disrupted sleep patterns. Montplaisir et al. (2006) found that over 80% of RLS patients had PLMD, highlighting the close relationship between these conditions.

Cardiovascular and metabolic disorders are also frequently associated with RLS. A comprehensive study by Winter et al. (2017) revealed a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease in RLS patients compared to the general population. This association is related to the chronic sleep disturbances and periodic limb movements common in RLS.

Psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are also commonly comorbid with RLS. A study by Becker et al. (2008) demonstrated a significant association between RLS and depressive symptoms. The chronic nature of RLS and its impact on sleep and quality of life are likely contributing factors to this comorbidity.

Renal disease, particularly end-stage renal disease, and associated iron deficiency have been linked to RLS. A study by Goffredo Filho et al. (2007) showed that RLS is more prevalent in hemodialysis patients, indicating a potential relationship between renal function and RLS.

Iron deficiency anemia is another notable comorbidity. Earley et al. (2000) conducted a study that found that iron supplementation could improve RLS symptoms in patients with low ferritin levels, suggesting a role of iron deficiency in the pathophysiology of RLS.

In summary, RLS is associated with a range of comorbidities, including sleep disturbances, cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, psychiatric conditions, renal disease, and iron deficiency anemia. These comorbid conditions can influence the severity and management of RLS.

Risk Factors

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) is influenced by various risk factors that span genetic, physiological, and lifestyle aspects. Understanding these risk factors is crucial for identifying individuals at higher risk and guiding preventive and management strategies.

Genetic predisposition is one of the primary risk factors for RLS. Studies have identified specific genetic markers associated with the disorder. A significant study by Winkelmann et al. (2007) established a genetic link through a genome-wide association study that identified common variants in three genomic regions associated with RLS. This research underlined the hereditary nature of RLS, indicating that individuals with a family history of RLS have a higher risk of developing the condition.

Iron deficiency is another well-established risk factor. Research by Earley (2003) found a strong correlation between low iron levels, particularly in the brain, and the occurrence of RLS. This study suggested that iron supplementation could be an effective treatment for some patients, particularly those with low serum ferritin levels.

Pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, has been identified as a risk factor for RLS. A study by Manconi et al. (2004) observed an increased prevalence of RLS in pregnant women, with symptoms typically improving postpartum. This relationship is thought to be related to hormonal changes and possible iron deficiency during pregnancy.

Chronic diseases such as renal failure and diabetes have also been linked to an increased risk of RLS. Gao et al. (2009) showed a higher prevalence of RLS in patients with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, diabetes has been associated with a higher risk of RLS, as shown in research by Merlino et al. (2007), possibly due to peripheral neuropathy or vascular complications.

Certain medications, particularly those affecting dopaminergic or serotonergic pathways, can exacerbate or trigger RLS. A review by Trenkwalder et al. (2008) highlighted the potential for certain antidepressants and antipsychotic medications to induce or worsen RLS symptoms.

In summary, the risk factors for RLS include genetic predisposition, iron deficiency, pregnancy, chronic diseases such as renal failure and diabetes, and certain medications. Understanding these risk factors is essential for the early identification and management of RLS.

Case Study

Presenting Concerns: Nicholas, a 19-year-old college student, presented to the clinic with complaints of uncomfortable sensations in his legs, described as a crawling and tingling feeling, disrupting his ability to sit still during evening classes and affecting his sleep quality. These symptoms occurred intermittently over the past year but became more frequent and severe over the past three months.

Clinical Findings

- Symptoms:Nicholas reported an overwhelming urge to move his legs, especially during periods of inactivity, such as sitting in lectures or lying in bed at night. He described the sensations as "crawling" and "tingling" inside his legs, temporarily relieved by movement.

- Sleep Disturbances:Difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings due to leg discomfort, leading to excessive daytime sleepiness.

- Psychological Impact:Increased stress and anxiety, particularly regarding his academic performance and sleep deprivation.

- Family History:Nicholas reported that his mother experienced similar symptoms, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition.

Diagnosis Based on the DSM-5-TR criteria for Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), Nicholas's symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of RLS:

- An urge to move the legs, accompanied by uncomfortable sensations.

- Symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity.

- Partial or total relief by movement.

- Symptoms are worse in the evening or night.

- The symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Management and Treatment

- Education and Lifestyle Modifications: Nicholas was educated about RLS and advised on lifestyle modifications, including regular exercise, maintaining a regular sleep schedule, and avoiding caffeine and alcohol.

- Pharmacological Treatment: Considering the severity of symptoms and impact on sleep, a trial of a low-dose dopaminergic agent was initiated.

- Follow-Up and Monitoring: Regular follow-up appointments were scheduled to monitor the effectiveness of treatment andmake any necessary adjustments.

Outcome After three months, Nicholas reported a significant reduction in the frequency and severity of his symptoms. He experienced improved sleep quality and could better concentrate during his evening classes. The dopaminergic agent was well-tolerated with no significant side effects. Nicholas was encouraged to continue his lifestyle modifications and report any changes in his symptoms.

Conclusion This case of Nicholas, a 19-year-old college student with RLS, highlights the importance of early recognition and management of RLS, especially in younger individuals. Combining pharmacological treatment and lifestyle modifications can significantly improve symptoms and overall quality of life. Regular monitoring and adjustments in the treatment approach are crucial in managing this chronic condition effectively.

Recent Psychology Research Findings

Recent psychology research has increasingly focused on the psychological aspects and impacts of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS), revealing significant insights into the condition's effect on mental health and quality of life.

One of the critical areas of focus is the relationship between RLS and mental health disorders, particularly depression and anxiety. A study by Winkelman et al. (2005) found a strong association between RLS and major depressive disorder. The study, involving an extensive cross-sectional survey, demonstrated that individuals with RLS had a higher prevalence of depression, indicating a need to consider mental health in RLS management.

Anxiety disorders have also been linked to RLS. Research by Hornyak et al. (2005) examined the prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with RLS. Their findings revealed a significantly higher rate of anxiety disorders among RLS patients compared to the general population. This study highlights the importance of evaluating and treating anxiety symptoms in RLS patients.

Sleep disturbance, a common symptom of RLS, has been extensively studied for its psychological impacts. A study by Cho et al. (2015) investigated the impact of RLS on sleep quality and found that RLS patients had significantly poorer sleep quality, more severe insomnia symptoms, and higher levels of daytime sleepiness than those without the disorder. This research emphasizes the critical role of sleep management in RLS treatment.

Quality of life in RLS patients has also been a subject of research. A study by Abetz et al. (2004) used validated quality-of-life instruments to assess the impact of RLS on patients' everyday lives. The results showed that RLS significantly impairs quality of life, with patients reporting difficulties in both personal and professional domains.

Cognitive functioning in RLS patients has been explored in recent research. A study by Fulda and Schulz (2001) examined cognitive performance in individuals with RLS. Their findings suggested that RLS may impair certain aspects of cognitive functioning, particularly those related to attention and executive function.

Collectively, these studies highlight the multifaceted impact of RLS on psychological well-being, underlining the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses the disorder's physical and psychological aspects.

Treatment and Interventions

The treatment and intervention strategies for Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) are diverse and tailored to each case's severity and specific characteristics. Research has focused on pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to manage this condition effectively.

Pharmacological treatments are a mainstay in managing RLS, particularly for moderate to severe cases. Dopaminergic agents, such as pramipexole and ropinirole, are commonly used. A study by Trenkwalder et al. (2008) evaluated the efficacy of pramipexole in RLS treatment, finding significant improvements in symptom severity and sleep quality. Another study by Garcia-Borreguero et al. (2016) highlighted ropinirole's effectiveness, noting its ability to alleviate RLS symptoms and improve sleep.

Alpha-2-delta ligands, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, have also been used effectively in RLS treatment. A randomized controlled trial by Garcia-Borreguero et al. (2013) demonstrated that pregabalin significantly reduced RLS symptoms and improved sleep quality compared to placebo.

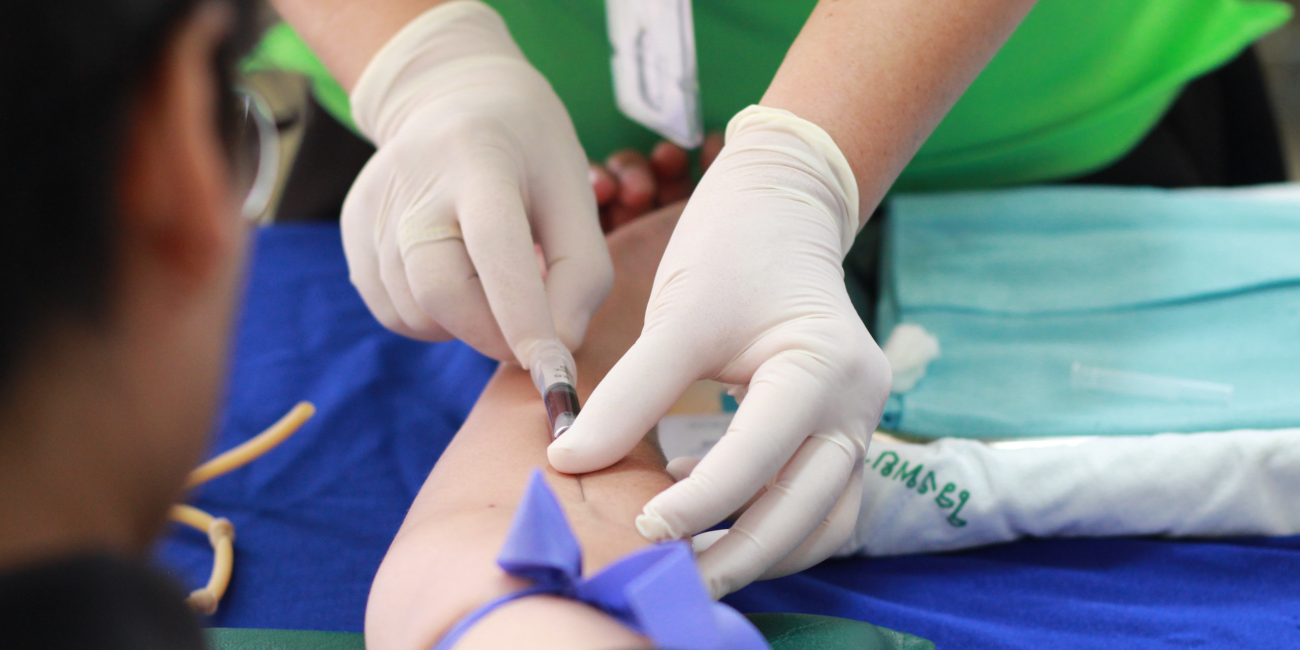

Iron supplementation is another pharmacological approach, particularly in patients with iron deficiency. A study by Earley et al. (2000) showed that intravenous iron dextran could significantly reduce RLS symptoms in patients with low serum ferritin levels.

Non-pharmacological interventions are vital, especially for mild cases of RLS or as adjuncts to medication. Regular exercise and good sleep hygiene are commonly recommended. A study by Aukerman et al. (2006) found that moderate aerobic exercise and lower-body resistance training could reduce RLS symptoms. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been explored for its benefits in managing RLS, mainly improving sleep and coping strategies. A study by Hornyak et al. (2006) found that CBT targeted at RLS could help reduce symptom severity and improve sleep.

Pneumatic compression devices have also been studied as a non-pharmacological treatment. A trial by Lettieri et al. (2009) reported that pneumatic compression could offer significant relief from RLS symptoms, especially in patients who are intolerant or unresponsive to pharmacological treatments.

In summary, the treatment of RLS is multifaceted, often involving a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. The treatment choice is tailored to individual patient needs, considering the severity of symptoms and associated comorbidities.

Implications if Untreated

If Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) remains untreated, it can lead to several long-term implications affecting physical and mental health. Research has highlighted the potential consequences of untreated RLS, which range from sleep disturbances to impacts on quality of life and mental health.

One of the most immediate and significant implications of untreated RLS is chronic sleep disturbance. A study by Hornyak et al. (2006) emphasized that individuals with untreated RLS often experience difficulties in initiating and maintaining sleep, leading to chronic sleep deprivation. This can result in excessive daytime sleepiness, impacting daily functioning and quality of life. Additionally, chronic sleep deprivation has been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, as noted in a study by Winkelman (2008), indicating potential long-term health risks.

The impact of untreated RLS on mental health is also noteworthy. A longitudinal study by Becker et al. (2004) found a significant association between untreated RLS and the development of depressive and anxiety disorders. This relationship is thought to be due to the chronic distress caused by persistent RLS symptoms and the resultant sleep disturbances.

Quality of life is another area significantly affected by untreated RLS. A study by Abetz et al. (2004) using validated quality-of-life instruments found that individuals with untreated RLS reported lower quality-of-life scores, particularly in physical and emotional well-being domains. This decrease in quality of life can be attributed to the chronic, distressing nature of RLS symptoms and their impact on sleep and daily activities.

Furthermore, untreated RLS can exacerbate other comorbid conditions. For instance, a study by Lettieri and Eliasson (2009) suggested that untreated RLS could worsen symptoms of comorbid conditions like hypertension and diabetes, potentially due to the effects of chronic sleep deprivation and the resultant physiological stress.

In conclusion, untreated RLS can lead to chronic sleep disturbances, increased risk of mental health disorders, decreased quality of life, and exacerbation of comorbid conditions. These implications underscore the importance of early diagnosis and effective management of RLS to mitigate these potential long-term effects.

Summary

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) presents a challenging condition in terms of diagnosis and its impact on individuals' lives. Historically, RLS was often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, partly due to a lack of awareness and understanding of the condition. Over time, however, the perspective on RLS has evolved, with increased recognition of its prevalence and impact. This shift towards a more inclusive and compassionate understanding is evident in the extensive research and evolving diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-5-TR.

The diagnostic challenges of RLS primarily stem from its subjective symptoms and the need for patient self-reporting. Studies like those by Allen et al. (2003) have emphasized the importance of careful clinical evaluation to differentiate RLS from other conditions with similar presentations. The evolution of RLS diagnosis over time reflects a growing understanding of its distinct features and the necessity of a patient-centered approach to diagnosis and treatment.

The impact of RLS on personal identity, relationships, and daily functioning is profound. A study by Lee et al. (2008) highlighted how RLS can disrupt interpersonal relationships, with symptoms often leading to tension and misunderstanding among family members. The nocturnal nature of the symptoms can particularly strain spousal relationships, as partners may be affected by disrupted sleep patterns and the resultant stress.

RLS can also profoundly affect individuals' ability to function in daily life. Research by Winkelman (2006) illustrated how the sleep disturbances caused by RLS can lead to daytime fatigue, impacting work performance and social engagement. This can erode confidence and contribute to a sense of isolation, further exacerbating the psychological distress associated with the condition.

Moreover, the chronic nature of RLS can influence one's self-perception and identity. As noted in a study by Hornyak et al. (2007), patients often experience a loss of control over their bodies and lives, leading to frustration and helplessness. This can affect self-esteem and overall mental well-being.

In conclusion, Restless Legs Syndrome is a complex condition that challenges both diagnostic processes and the lives of those it affects. The evolution in understanding RLS has led to more compassionate and inclusive approaches to diagnosis and treatment, acknowledging the profound impact of this disorder on personal identity, relationships, daily functioning, and confidence.

References

Abetz, L., Allen, R., Follet, A., Washburn, T., Earley, C., Kirsch, J., & Knight, H. (2004). Evaluating the quality of life of patients with restless legs syndrome. Clinical Therapeutics, 26(6), 925–935.

Allen, R. P., Picchietti, D., Hening, W. A., Trenkwalder, C., Walters, A. S., & Montplaisir, J. (2003). Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Medicine, 4(2), 101-119.

Allen, R. P., Walters, A. S., Montplaisir, J., Hening, W., Myers, A., Bell, T. J., & Ferini-Strambi, L. (2014). Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(11), 1286–1292.

Aukerman, M. M., Aukerman, D., Bayard, M., Tudiver, F., Thorp, L., & Bailey, B. (2006). Exercise and restless legs syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 19(5), 487–493.

Becker, P. M., Sharon, D., & Ondo, W. (2004). Encouraging initial response of restless legs syndrome to pramipexole. Neurology, 63(10), 1942-1943.

Becker, P. M., Sharon, D., & Risk, M. (2004). Depression, anxiety, and daytime dysfunction in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine, 5(3), 237–246.

Cho, S. J., Hong, J. P., Hahm, B. J., Jeon, H. J., Chang, S. M., Cho, M. J., & Lee, H. W. (2015). Restless legs syndrome in a community sample of Korean adults: Prevalence, impact on quality of life, and association with DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. Sleep, 38(8), 1205–1213.

Connor, J. R., Wang, X. S., Patton, S. M., Menzies, S. L., Troncoso, J. C., Earley, C. J., & Allen, R. P. (2009). Decreased transferrin receptor expression by neuromelanin cells in restless legs syndrome. Neurology, 72(12), 1064–1070.

Earley, C. J. (2003). Clinical practice. Restless legs syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(21), 2103–2109.

Earley, C. J., Connor, J., Garcia-Borreguero, D., Jenner, P., Winkelman, J., Zucconi, M., & Allen, R. P. (2014). Altered brain iron homeostasis and dopaminergic function in Restless Legs Syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease). Sleep Medicine, 15(11), 1288–1301.

Earley, C. J., Heckler, D., & Allen, R. P. (2000). The treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextran. Sleep Medicine, 1(3), 231–235.

Fulda, S., & Schulz, H. (2001). Cognitive dysfunction in sleep disorders. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 5(6), 423-445.

Gao, X., Schwarzschild, M. A., Wang, H., & Ascherio, A. (2009). Obesity and restless legs syndrome in men and women. Neurology, 72(14), 1255-1261.

Garcia-Borreguero, D., Larrosa, O., Williams, A. M., Albares, J., Pascual, M., Palacios, J. C., & Fernández, C. (2013). Treatment of restless legs syndrome with pregabalin: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology, 80(3), 263-272.

Garcia-Borreguero, D., Silber, M. H., Winkelman, J. W., Högl, B., Bainbridge, J., Buchfuhrer, M., ... & Lee, H. B. (2016). Guidelines for the first-line treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease, prevention and treatment of dopaminergic augmentation: A combined task force of the IRLSSG, EURLSSG, and the RLS-foundation. Sleep Medicine, 21, 1-11.

Goffredo Filho, G. S., Gorini, C. C., Purysko, A. S., Silva, H. C., & Elias, I. E. (2007). Restless legs syndrome in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis in a Brazilian city. Sleep Medicine, 8(4), 395-400.

Happe, S., Reese, J. P., Stiasny-Kolster, K., Peglau, I., Mayer, G., Klotsche, J., ... & Berger, K. (2008). Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine, 9(3), 295-305.

Hornyak, M., Feige, B., Riemann, D., & Voderholzer, U. (2005). Periodic leg movements in sleep and periodic limb movement disorder: Prevalence, clinical significance, and treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 9(3), 169-178.

Hornyak, M., Grossmann, C., Kohnen, R., Schlattmann, P., & Voderholzer, U. (2006). Cognitive behavioural group therapy to improve patients' strategies for coping with restless legs syndrome: A proof-of-concept trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 77(2), 29-35.

Hornyak, M., Kopasz, M., Berger, M., Riemann, D., & Voderholzer, U. (2007). Impact of sleep-related complaints on depressive symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(12), 1786-1792.

Lee, D. O., Ziman, R. B., Perkins, A. T., Poceta, J. S., Walters, A. S., & Barrett, R. W. (2008). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with restless legs syndrome. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4(3), 282–292.

Lettieri, C. J., & Eliasson, A. H. (2009). Pneumatic compression devices are an effective therapy for restless legs syndrome: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled trial. Chest. 135(1), 74-80.

Manconi, M., Govoni, V., De Vito, A., Economou, N. T., Cesnik, E., Mollica, G., & Granieri, E. (2004). Pregnancy as a risk factor for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine, 5(3), 305-308.

Merlino, G., Fratticci, L., Valente, M., Del Giudice, A., Noacco, C., Dolso, P., ... & Gigli, G. L. (2007). Association of restless legs syndrome in type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. Sleep, 30(7), 866-871.

Montplaisir, J., Boucher, S., Poirier, G., Lavigne, G., Lapierre, O., & Lespérance, P. (2006). Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Movement Disorders, 21(3), 447-453.

Ohayon, M. M., & Roth, T. (2002). Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(1), 547-554.

Stefansson, H., Rye, D. B., Hicks, A., Petursson, H., Ingason, A., Thorgeirsson, T. E., ... & Stefansson, K. (2007). A genetic risk factor for periodic limb movements in sleep. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(7), 639-647.

Trenkwalder, C., Hogl, B., Winkelmann, J., & Kohnen, R. (2008). Recent advances in the diagnosis, genetics, and treatment of restless legs syndrome. Journal of Neurology, 255(4), 539-553.

Trenkwalder, C., Paulus, W., & Walters, A. S. (2008). The restless legs syndrome. The Lancet Neurology, 7(8), 738-748.

Winkelman, J. W. (2006). The evoked heart rate response to periodic leg movements of sleep. Sleep, 29(7), 930-935.

Winkelman, J. W. (2008). Cardiovascular consequences of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 3(3), 333-344.

Winkelman, J. W., Finn, L., & Young, T. (2005). Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome symptoms in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep Medicine, 6(6), 545-552.

Winkelmann, J., Schormair, B., Lichtner, P., Ripke, S., Xiong, L., Jalilzadeh, S., ... & Müller-Myhsok, B. (2007). Genome-wide association study of restless legs syndrome identifies common variants in three genomic regions. Nature Genetics, 39(8), 1000-1006.

Winter, A. C., Schürks, M., Glynn, R. J., Buring, J. E., Gaziano, J. M., Berger, K., & Kurth, T. (2017). Restless legs syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in women and men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 7(4), e013366.